Queen Victoria ascended to the throne in 1837, when Grace McIntosh was around nine years old. The city of Aberdeen was on the cusp of major expansion with its grand new thoroughfare of Union Street barely 40 years old. Between 1851 and 1901, the city’s population was to more than double from 75,000 to over 150,000.

In parallel with this growth in population came the physical expansion of the city: the first edition Ordnance Survey map of 1867 shows that this development fanned outwards from the historic centre of the Castlegate.

The west end of the city became the preserve of affluent families, their large houses financed by money made in the granite, textile, fishing and boatbuilding industries.

These industries were subject to the fluctuating fortunes of the national and increasingly global economy. In the early 1840s, Aberdeen’s textile industry employed about 14,000 people out of a total workforce within the city of around 30,000. The national economic collapse of 1848, linked mainly to speculation in railway shares, had a profound impact on the textile industry in Aberdeen as elsewhere.

There was a consequent knock-on effect for the rest of the economy and the people of the city. Indeed, the population growth of Aberdeen between 1851 and 1861 was only 2.6%, the lowest for any decade of the 19th century.

From this low point, the economy of the city did recover and diversify during the next fifty years. However, the improvement in the quality of life for the poorer sections of the population took much longer. For many, living conditions were dire and there is no doubt that the desperation associated with poverty drove many into a life of crime and vice to survive.

The city centre was densely populated with areas of older housing containing large pockets of significant deprivation and overcrowding. Addresses such as Guestrow, Gallowgate, Peacock’s Close, Justice Lane and Shuttle Lane became notorious not only because of the insanitary conditions but because of the attendant poverty and criminal ‘underclass’ that inhabited them.

Writing in the Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland in 1883, Francis H. Groome articulated the social consequences associated with the city’s rapid development,

“Some closes such as Smith’s and Peacock’s, adjacent to the east end of Union Street, exhibit the lower grades of civilisation only a few steps apart from the higher; and other places, such as the courts branching out from the Gallowgate, are about the dingiest and most unwholesome to be found anywhere in a British town”.

If Aberdeen was changing during the 19th century, then so too was society as a whole: it is difficult to overstate just how much reform took place during the Victorian era. From the poor law to prisons, temperance to abolition and from child labour to the Chartists, this was an age of reform and social agitation.

This was the backdrop to Grace’s life, but what of Grace herself?

Grace McIntosh was born c.1828 in Jack’s Brae, Aberdeen, her father George McIntosh was a weaver, his wife was possibly named Elizabeth. Grace was the fifth of seven children. Her siblings were John (b.1815), Ann (b.1816) George (b.1821), Helen (b.1825), Alexander (b.1831/32), Elizabeth (b.1835).

The family were Roman Catholic but no records of baptisms have yet been found. Consequently the dates of birth are estimates from other records and have to be taken with a pinch of salt. Similarly many of the records for Grace vary. She gives conflicting ages throughout her life: some are inflated to appear older whilst later ages are reduced. In a time before civil registration ages could appear fluid or be rounded up or down.

Grace first came to the attention of the Aberdeen magistrates in January 1839 her age was given as 11 years, she and her brother Alexander aged 7, were arrested for theft. Both were released after the charge was withdrawn. A month later Grace was again before the court for theft – this time with her elder sister Helen, aged 14. Grace was acquitted and released but her sister was sentenced to 60 days in prison, the maximum sentence that the magistrate in the Police Court could apply.

Grace was first described as a prostitute in official records in November 1842. She was possibly only aged 13 or 14 years and was convicted of stealing an item of woollen underwear from a seaman (Robert Gate) in a house in Jopp’s Lane, probably a house of ill repute, occupied by Catherine Beaton or Murray, a widow. Grace served 30 days in Aberdeen prison for this offence, her first taste of prison life.

A few months after her release, in March 1843, Grace was arrested on a charge of vagrancy. Once again she was recorded as a prostitute. It was not unusual for women engaging in prostitution to be arrested for vagrancy, especially if they had no fixed abode. Her age was recorded as 16 years (although her age was noted as 13/14 just a few months earlier) and described as of a ruddy complexion with flaxen hair and blue eyes. The Procurator Fiscal dismissed the case, and she was set free after two days in prison. So, three times previously Grace had been released without charge - however her luck was about to run out.

The next entry is almost a year later in February 1844. Her age was still recorded as 16 years but Grace herself said that she was 18 and living at Mutton Brae. The offence was theft and being by habit and repute a thief with previous convictions. The theft charge was for stealing two shawls and a cap from three different people on three separate occasions. Two victims were young children aged 6 and 8 yrs – a crime known as ‘child stripping’ when older girls preyed on vulnerable small children. Grace was described as dirty and ragged but sober. She was again recorded as a prostitute.

Although the 1841 Census shows Grace as living at home, her sister Elizabeth revealed to the court in 1844 that Grace had not lived with her father and siblings ‘for some considerable time’. Grace herself said that at the time of the offence she was living in the House of Refuge and had been there for eight days. The House of Refuge was opened in 1836 as ‘a temporary shelter for the utterly destitute’. It was a precursor to the poorhouses set up later around 1849.

For this crime, in front of judges Lords Moncrieff & Cockburn at the Spring Court in April 1844, Grace was sentenced to transportation to Australia for seven years. She was the third of her siblings to suffer this fate with Ann transported to Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania) in c.1831/2 for seven years & John to New South Wales in c.1834, also for seven years.

After spending 76 days in Aberdeen prison, Grace was transferred on 5 May by steamer to Millbank Prison on the banks of the Thames to await transportation. The Millbank Prison Register records that Grace was 16 years and single, that she could not read, her occupation is given as ‘Factory Servant’ but it also states that she ‘is supposed to have lived partly by crime about four years’. Her relatives or connections are recorded as ‘Indifferent’. Just over three months later her convict ship, the ‘Tasmania’, sailed on 8th September 1844.

Grace was one of four Aberdeen women transported together. The Tasmania held 191 convict women but two died on the voyage and would have been buried at sea – possibly a frightening and sobering experience for the young Grace, especially since one woman died from syphilis and was young at just 20 yrs old. The vessel arrived at Hobart, Van Diemen's Land, on 20th December 1844 after 103 days at sea.

On arrival in Van Diemen's Land Grace’s occupation was given as 'Farm Servant and Dairy Maid'. This was not a reflection of her previous occupation but an indication to the authorities in Hobart just what she might be employed as in this convict settlement. Most convicts were housed within the hulk ships offshore for a up to 6 months before removal on land. It is unknown if Grace also experienced this. It was noted, however, that she had a scar above her right eye.

Although she was recorded as quiet and hardworking Grace absconded from her workplace in June 1846 and again in February 1847 but was apprehended both times. During her years as a prisoner she was punished with hard labour and solitary confinement on seven separate occasions, the duration of these punishments ranged from 14 days to three months for the offences of absconding, neglect of duty, being out after hours and absent without leave and, finally, being drunk and disturbing the peace in September 1850. Consequently, during her convict period she was imprisoned at Cascades Female Factory in Hobart, and in Launceston Female Factory in the North of the island - notoriously hard female prisons.

Grace married another convict Aaron Masters in August 1847 in Van Diemen's Land – her age was recorded as 23 but in reality she was 18 or 19 years old. Her husband, whom she always referred to as 'Ernest' (quite possibly as a pet-name), was baptized in March 1795 and was at least 30 years her senior. He was originally from Cornwall and had been convicted of stealing a cow in 1839 and sentenced to 10 years transportation. He had left a wife and five children in Cornwall.

Aaron Masters had been a miner in Cornwall and following his discharge he pursued a career as a copper miner in Australia. Grace and Aaron had a child, Henry, b.1848. However, it is likely that Henry died as no later information has been found.

Grace was granted a Certificate of Freedom in April 1851. By August 1851 Grace and her husband were no longer together: a notice in the local paper cautioned against giving her credit as her husband claimed that she had ‘left her home without provocation’. At the time, this type of newspaper disclaimer was common practice when couples separated as it effectively absolving the man of any debts that his wife might incur.

On 25 March 1852 Grace sailed to Melbourne aboard the ship The City of Melbourne. By March 1854, then aged 25, she had enough money to book a passage to London aboard the ship The Prince Alfred, a 3-4 month voyage in steerage, the lowest class. This would probably have cost £18 … approximately £1500 in today's money. It is unknown how she procured enough money for the passage back to Britain but perhaps it isn’t hard to imagine given her history.

It is likely that Grace began offending again soon after her arrival back in Aberdeen as in 1854 there is reference to a previous court appearance, but the pages are missing for that particular entry. By October 1854 Grace was again involved in crime with an accomplice, Elizabeth Sheriffs, a known prostitute.

They were accused of theft of a number of items including a gown, shawls, stockings, bedgowns and caps etc from an attic room of a house in McCook’s Court belonging to a female acquaintance they had met in a lodging house in Shuttle Lane and who they had gone drinking with. She testified they had waited for her to go to sleep then taken her belongings. Some of the items were pawned and the money acquired was spent on drink by the two accused. Grace told the Police when arrested that she could not help it – and, "that they could not do worse to her than they had done before", quite possibly a reference to punishment of transportation that she had endured.

Grace experienced transportation at a time when questions were being asked about its utility. Attitudes towards punishment were changing: for example, religious groups like the Quakers and the Evangelicals were highly influential in promoting ideas of reform through personal redemption.

Transportation had come to be seen as an inhumane punishment and was replaced by the convict prison system from 1853 onwards, with the Penal Servitude Act of 1857 providing the corresponding legal framework. The minimum length of sentence under this new Act was three years.

Under the terms of this system, a prisoner’s sentence comprised three distinct parts: firstly, an initial period of separate confinement, which lasted between six and nine months; secondly, public works, which included occupations such as net-making, carpentry, sack-making, weaving, tailoring and washing; and finally, release on licence during which time the convict would have to report to the police on a regular basis.

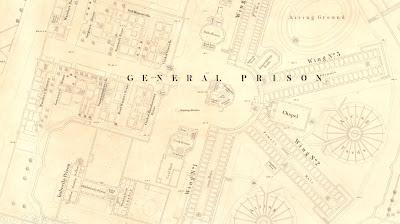

This change in the convict system required modified prisons. The General Prison for Scotland (with which Grace was to become familiar) was located at the expanded facility at Perth. Anyone sentenced to longer than nine months would be sent there.

|

| Reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland |

In the first edition OS map shown above, the individual cells in the wings of the prison (to cater for separate confinement) can be seen quite distinctly.

In her court papers of November 1854, Grace gave her age as 25 years, and her address was recorded as East North Street. In January 1855, her name had appeared on a Return of Prostitutes in Aberdeen.

The creation and existence of this document is evidence of the social and moral soul-searching that the authorities were undertaking at the time. Indeed, a few years later, in 1860, a report was published by the Prison Board of Aberdeenshire with the title “On The Repression of Prostitution” which was part of the preparation for The Aberdeen Police and Waterworks Act and the Public Houses (Amendment) Act, both of 1862, which provided the police with greater powers to deal with vice in the city.

Between 1862 and 1864 Grace was in court nine times for breaches of the peace, Contravention of the Public House Act – which constituted being drunk and disorderly. On another occasion she was also accused of stealing a silver watch – but after a week in Aberdeen Prison she was released without charge.

In 1864 Grace was convicted of theft of a gown and being a habit and repute thief with previous convictions. She was given an eight year prison sentence and was sent to Ayr Prison, after and initial stretch of 146 days in Aberdeen Prison.

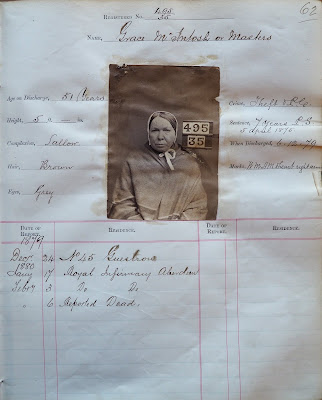

In April 1875 – Grace (whose age was recorded variously as 47 and 51 in two different sources) along with Mary Murray (age 51) were convicted of stealing £30 in cash from James Grant, a flesher/butcher whilst in a house in Rettie’s Court. He lived in Union Lane, Aberdeen.

Although Grace had served her sentence for her previous convictions which resulted in transportation they were once again cited and she was given seven years penal servitude while Murray, her accomplice, received just eight months imprisonment. The prison register notes that Grace had a tattoo on her right arm – the initials UM and HM and a heart – which might suggest that Henry Masters was not her only child.

Grace was liberated on licence on 6 December 1879. The register of Returned Convicts for Aberdeen (see image at the bottom of the page) records that she was housed at the Victorian Lodging House in Guestrow from where she was sent to the Aberdeen Royal Infirmary just over a month later on 17 Jan 1880.

Grace died on 4 February 1880 – her death certificate records the cause of death was "bronchitis and emphysema (several years)" and her age is given as 52 years. Three days later, on 7 February 1880 she was interred in the poor section of Nellfield Cemetery at the expense of the council - a sum of 3 shillings.

No comments:

Post a Comment